Woodland Cultural Centre (WCC) will re-open the Mohawk Institute Residential School as an interpretive historic site and educational resource as part of its National Day for Truth and Reconciliation programming on Tuesday, September 30, 2025.

After its closure in 1970, the former institute sat unused for several decades, however in 2013, major roof leaks caused significant and costly damage to the building, prompting the WCC to conduct community consultations to determine whether to preserve the site. The response was overwhelming, 98 per cent of those consulted were in support of restoration efforts, leading to the launch of the Save the Evidence campaign.

Now, more than ten years and $26 million later, the building has been repaired to ensure the physical evidence of the residential school will never be forgotten. From here on out, those who tour the building will encounter survivor accounts, historical facts and figures, recreated rooms and classrooms, and authentic artifacts from the building’s time as a school.

“This will be a Canadian Museum of Conscience, the first one in this country, so we’ll never go down that path again of what happened to us,” said Amos Key Jr., a Councillor for Six Nations of the Grand River and member of the WCC Board of Directors.

Ahead of the grand opening, nearly 100 people, including survivors and their family members, were invited to attend a pre-opening event this past Monday.

Before sending everyone on their self-guided tours, Roberta Hill, who was just 6-years-old when she first attended the Mohawk Institute, shared a bit about her experience with those in attendance.

“The officials really didn’t care about what we felt or how we were living, that wasn’t the agenda,” she said. “The agenda was to take away your culture, your language, your identity, so this was the perfect place, I guess, for the government and church to do that.”

Hill said that while it was difficult to be in the building, the newly renovated institute is a step toward correcting the narrative about the country’s residential school system.

“This is our history, but it’s also Canada’s history and we were very much players in it. …This was portrayed as some place that was really good for children, but it wasn’t,” she said. “History needs to be written by those who were involved in it, not people who were in control. We are the victims. We need our say. We need our voices to be heard. …How are you going to reconcile anything unless you’re truthful about what happened?”

“We need you to understand and we need you to listen,” continued Hill. “I know you can’t change the past, and we’re not asking anybody to change the past, but moving forward, [we need you to] understand that this can happen again. It can happen again unless you’re really vigilant.”

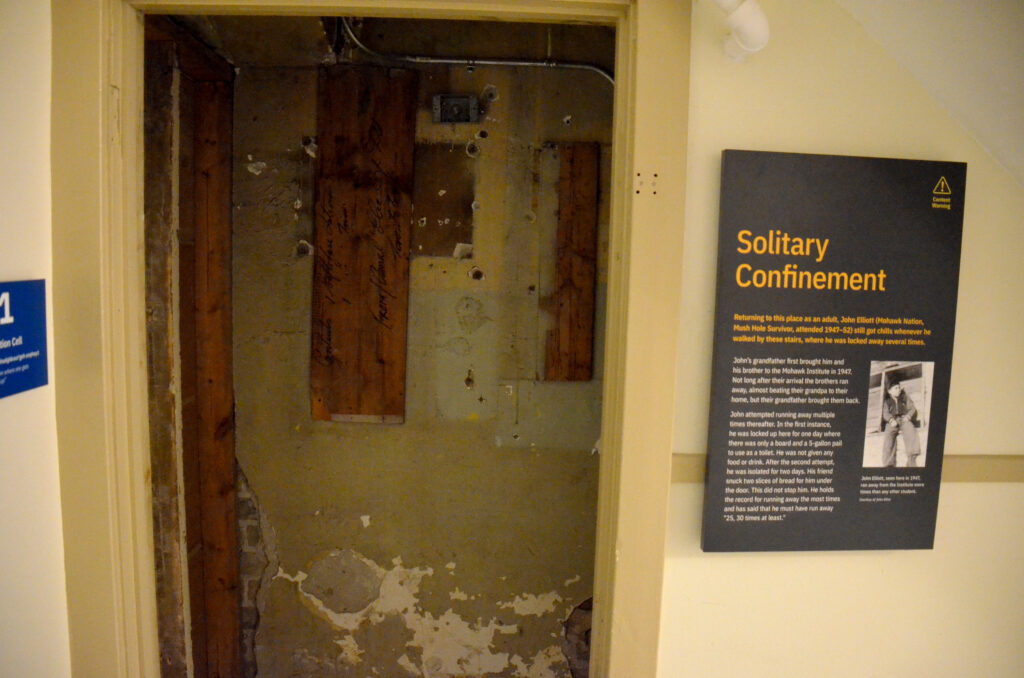

Following the speeches, many spent their time solemnly taking everything in, looking at the gallery wall of survivors and listening to their first hand accounts at various audio stations, or confronting spots of forced isolation.

“There’s audio listening stations in the building with first hand accounts from survivors. We also have a few different video installation pieces, one in particular is a discussion between a young Indigenous girl and Duncan Campbell Scott, essentially questioning him about the actions of him and his department. In the laundry room, there is a visual installation showing three generations of women from one family sitting around a dinner table and talking about how the institute impacted them,” said Heather George, Executive Director for the WCC. “I think that one of the most meaningful things though, are the direct quotes from the survivors that are throughout the building. They’re on the furniture and on the walls, and I think those are really a reflection of the survivors and their exact experiences. It’s the history that they are part of and what they lived through, and it’s one of the most powerful elements of the interpretation.”

George said that she hopes people who tour the building will walk away with a better understanding of the history that happened at the Mohawk Institute, and that people will be motivated to do more work around truth and reconciliation.

“I think that this is now a place that cares for survivor stories and it ensures that they’re not forgotten, and that is a great honour and a great responsibility,” she said. “I’m honestly interested to see how people experience the space, what they’ll take from it and how it changes their thinking. I’m really hoping that we’ll have the ability to change people’s hearts and their minds, and then open them up to engaging with more work around reconciliation.”

George added that while the reopening has been a long-time coming, she’s grateful for everyone who stuck by and stayed dedicated to the project.

“I would say the biggest emotion I’m feeling right now is gratitude because it took a lot of work and a lot of people’s emotional energy,” she said. “ So much work and so much care went into this project and I just hope that it’s something the survivors feel really reflects their experience.”

Jesse Squire, who works with the Survivors’ Secretariat, said that it was good to see that the former Mohawk Institute has become a place to educate the public rather than remaining frozen in time.

“They’ve taken the building and turned it into something that’s educational as opposed to leaving it stuck in the era of the residential school, but at the same time, they’ve honoured the history,” he said. “It’s really interesting to see how much it’s changed and how much is new, but there’s also so much that has been preserved. The bricks are the same, the floors, the walls and the internal structure itself are the same, and so I’m really proud of them for that. I know it’s been a long time coming and that there have been hurdles and obstacles to get where we are now, and so the fact that it’s almost complete is such a nice feeling.”

Squire added that while the renovation of the Mohawk Institute certainly won’t make it any easier for survivors to walk through, he hopes they will see how important it is for future generations to learn from.

“We work a lot with our survivors and when we’ve brought them here in the past, many of them haven’t been able to complete a full tour because they’re reminded of the trauma,” he said. “But I think the way that it’s been redone now will allow us to take them in one room at a time and one floor at a time, and just give them the time and space to absorb it all. I think it will still be hard because they have to relive everything, especially now that the writing is literally on the walls, but I’m hopeful that in the long run, they’ll be able to see it as a living legacy.”

Operating from 1828 to 1970, the Mohawk Institute was the longest-running residential school in Canada. First established by the New England Company, a British Anglican missionary society, the Canadian government assumed daily operations of the institute in 1929, although Anglican influence remained in place until its closure on June 27, 1970.

The residential school system was designed to assimilate Indigenous children by cutting ties to their language, culture, society and traditions. While many may have started out as an optional program, in 1920 Duncan Campbell Scott, Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs, made attendance mandatory for children between the ages of seven and 15.

According to the Survivors’ Secretariat, an estimated 15,000 students from more than 60 communities were sent to the residential school, frequently known as the “Mush Hole.” Many survivors have since shared accounts of the the emotional, physical and sexual abuse endured during their time there. At least 105 children died while enrolled.

Kimberly De Jong’s reporting is funded by the Canadian government through its Local Journalism Initiative.The funding allows her to report rural and agricultural stories from Blandford-Blenheim and Brant County. Reach her at kimberly.dejong@brantbeacon.ca.