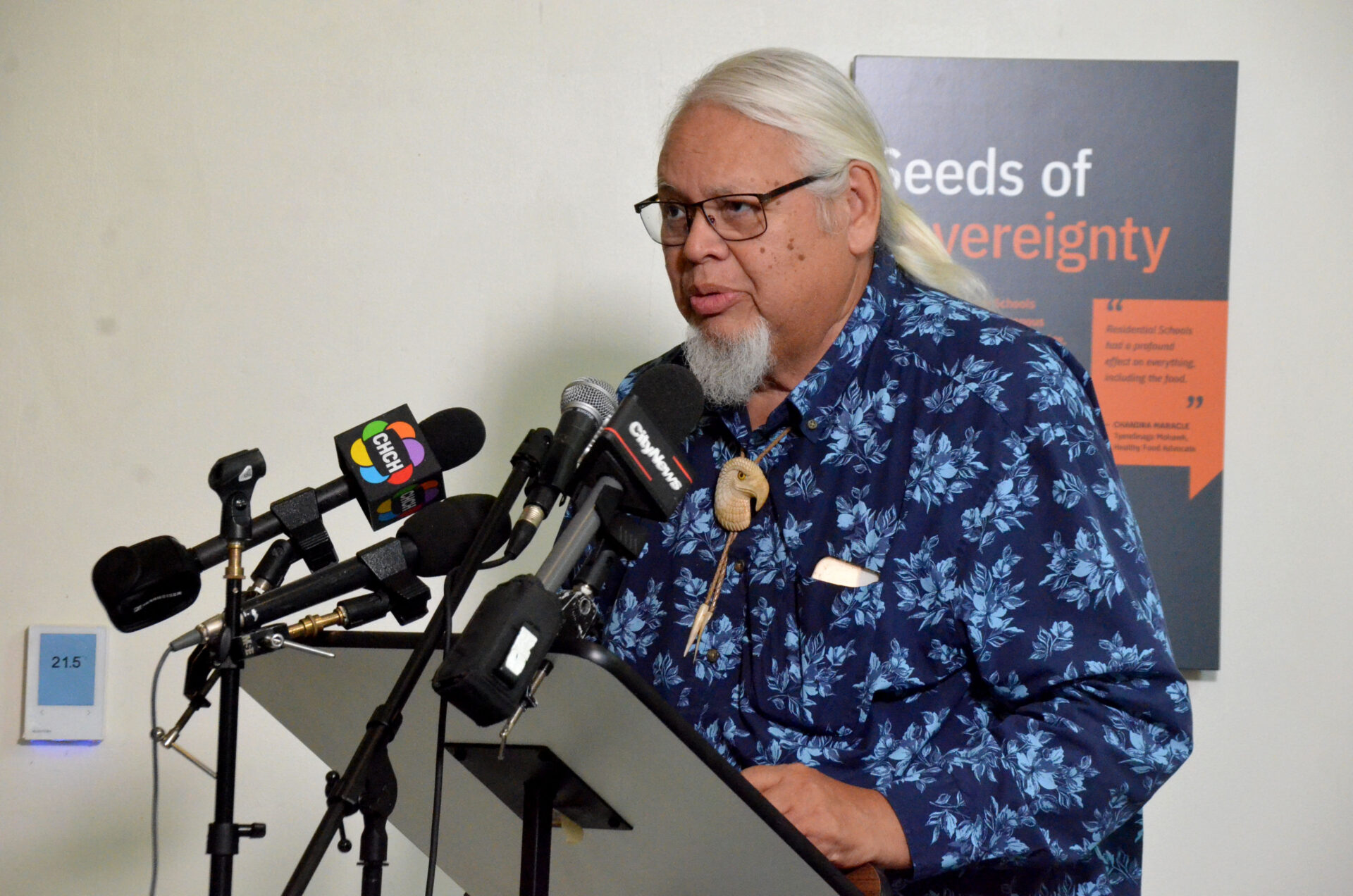

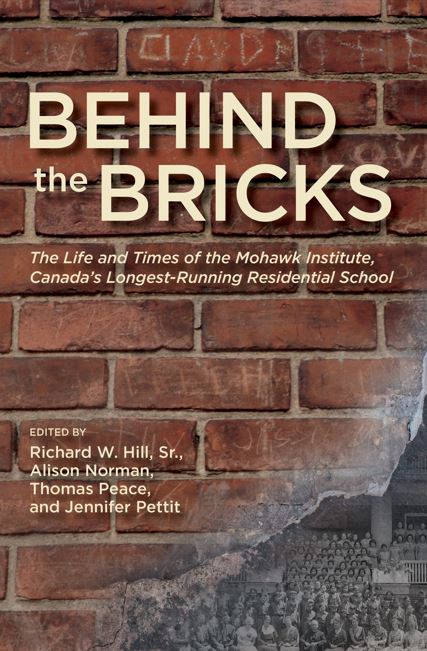

With the release of the book, Behind the Bricks: The Life and Times of the Mohawk Institute, Canada’s Longest-Running Residential School, the editors and many contributors, including survivors, shared personal stories, unvarnished accounts and truthful insight into the residential school, which operated from 1828 to 1970 in Brantford, Ontario.

Richard W. Hill Sr., a historian, and one of the editors of the book, as well as a citizen of the Beaver Clan of the Tuscarora Nation of the Haudenosaunee at Grand River, described his journey in first discovering his roots, and ultimately leading to his research into the Mohawk Institute residential school.

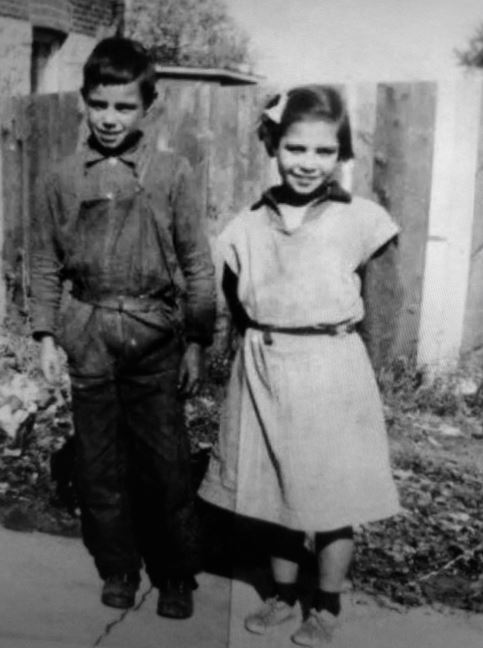

“I was born in Buffalo…my father was a Mohawk from Canada. My mother’s from the Tuscarora Nation in Lewiston, New York. So, when they got together, my dad followed the work, coming to Buffalo. I had three brothers and a sister, but [eventually left] Buffalo quite early to move to a place called Grand Island…which is in the middle of the river between New York and Ontario. And in many ways, that’s the way I felt my life went. I felt like a ping pong ball going back and forth between my mother’s and dad’s communities…and not really feeling like I belonged anywhere,” said Hill.

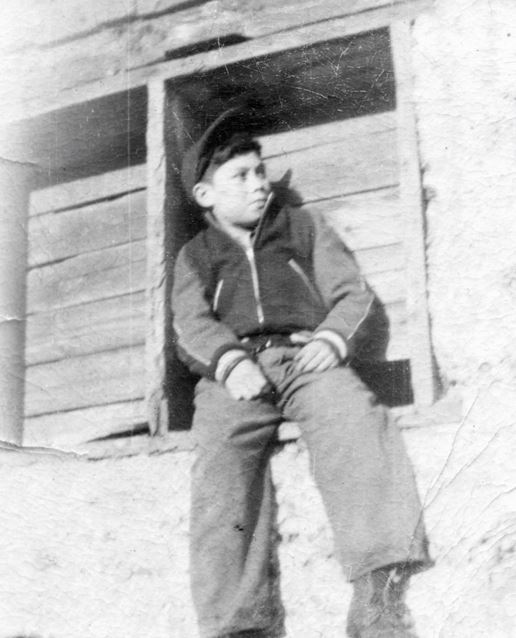

At a very young age, Hill felt the sting of loss, however, giving him a perspective on life and death.

“My real journey began when my dog died when I was five years old. It was hit by a car on the last day we’re moving out of the city to move into the country. It made me think about life and death, and about the difference between city life and country life. Moving to Grand Island, which allowed my dad to pick up his tradition of farming. Both my dad’s and my mother’s parents insisted on farming. So being in the garden, in the fields, in the woods, chasing deer and other animals, hunting, and being in the river to fish, all began to somehow connect within me,” he reflected. “My ancestors used to be in the same place, and I could reimagine them here in my head, these men in their moccasins and their leather outfits, walking through the woods. It actually helped me [discover that there is] something more to life than going to school and making a living.”

However, Hill came to face another tragedy with the death of his brother, which pushed him to connect with who he was.

“It wasn’t until my brother was killed in a car accident in 1970 that it forced me to ask myself, ‘What kind of person do I want to be?’ And I couldn’t resolve the grief over my brother’s death. He was only a year older than I was. I went to the church to talk to priests, I went to the synagogue to talk to rabbis, and even spoke to some doctors. But it wasn’t until I went to Chicago. They just had the Democratic National Convention in Chicago which [saw] the largest police riot in American history…there was a protest of native people trying to re-occupy some land,” recalled Hill. “So, I went down there, despite being a little nervous…I made my way to the native center in Chicago connected with some people there. I watched the singing and dancing, and it was just the way that people took me in. It didn’t matter where I was from or how I grew up. They made me feel like I mattered. With that, they told me that I needed to find my roots. I needed to go back to my people and connect with them.”

After that, Hill embarked on a journey to find his roots.

“I made my way back to Six Nations and talked to those we called the Long Boat people. They are those that keep the tradition [and when I spoke with them] everything they said made sense to me about the feelings I was having, especially what happens to somebody when they pass away,” Hill recalled. “What they said clicked with me and I wanted to know more. But, at the same time, I was a little angry. How come I didn’t know this growing up? So, at the age of 20, I decided to find out about myself and start on this journey. I was fortunate that in my generation there were many people like that that we could turn to [and] who were willing to share information.”

Nevertheless, Hill started to realize his path, and opportunities to reconnect with his roots started to materialize.

“I was watching TV and saw this long-haired native man talking about a conference at the University of Buffalo. I knew I had to go, so I jumped on a bus and went. It was startling. There were what seemed like 500 Indigenous people there, including some great speakers. But there were also a lot of people just like me, who were wondering who we were and how we got into this situation,” said Hill. “We were looking for answers, and they were all there. It was a springboard for my future. I’ve always felt that Indigenous Studies programs at universities and colleges are the place to start learning about these things. I met Oren Lyons, an Onondaga Chief, and John Mohawk too who would both become my mentors. We would then mentor each other because we didn’t grow up steeped in our traditions or speaking our native languages…we were students, learning together about our heritage.”

Hill would become immersed in learning about his heritage and educating others. He would go on to get his Master’s Degree in American Studies from the State University of New York at Buffalo and become an Assistant Professor of Native American Studies at SUNY Buffalo. However, he would

“I attended a reading of the Great Law of Peace at the Onondaga Nation. It’s our foundational governing structure. I was completely amazed and impressed when speakers held up replicas of our wampum belts. But they explained that the originals had been taken by scholars and were locked away in museums, which shook me. I decided to make it my life’s mission to help recover these wampum belts and return them to our people. I’m proud to report that, thanks to the work of many, we’ve recovered over 400 different belts and items. It’s like a treasure trove of knowledge that has come back to us,” he said.

Through the years, Hill held various roles, as the Assistant Director for Public Programs, National Museum of the American Indian at the Smithsonian Institution and the Museum Director at the Institute of American Indian Arts, in Santa Fe, New Mexico, as well as learning about the tragic stories of the residential schools at his time with the Woodland Cultural Centre. However, fast forward to 2018, Hill was asked to do an exhibition on the Mohawk Institute, ultimately creating and publishing Behind the Bricks.

“It was quite a challenge, because they gave me nine months to do this. It was a pretty sharp learning curve, digging around in the archives, looking at records, testimony and talking to survivors. All of a sudden, I realized there’s a huge story that’s been hidden from our people. How was I supposed to bring that out in nine months?’ So out of my nervousness, I found a few historians online who either wrote about the Institute or were doing work on residential schools, and called them up to see if they were willing to share their research,” Hill recounted. “It was really amazing to find how eager they were, because the story’s been there and the research has been there, but it has never really reached the forefront, and certainly with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and all of that, it helped to focus attention on that. But here I was at Canada’s oldest and longest-running residential school, and I didn’t know what the story of the place was. So, in doing that research since then, we’ve been able to pull it together, and we’re going to have an exhibition to interpret the meaning of this place. So along with the work that the scholars and I did to gather our minds to say what we know about this place, whether they have lingering questions, and how we can help the public better understand the nature, the psychology and the consequences of the Mohawk Institute.”

Hill, who was recently appointed as an honorary officer of the order of Canada for his contributions to indigenous art history and culture, discussed the process of developing this important book.

“I was reluctant to rush into publishing because I knew how complicated this story was. I see our work as being like a spider web. We have a core group with our own research and resources, but we’re also connected to the next ring of people who have more information, and then to the archives and museums. By working together, everyone was able to use their personal and professional contacts to let the information flow,” he explained. “As editors, our job was to look at it all and make sure the facts were consistent and correct. Our team worked diligently on this, and it was a labor of love for everyone. We know we won’t make a lot of money writing history books, but we decided to donate all the proceeds from the book to the Woodland Cultural Centre and the Mohawk Institute. We did this as a public service, for the sake of the future. Our goal is for people in my community, the Haudenosaunee communities, and in universities—as well as government, churches, and the general public—to finally see the full scope of what an institution like the Mohawk Institute represents.”

Hill then reflected on how in doing the research and interviews, it started to become personal.

“Imagine you’re interviewing people your own age or maybe a little older, and they’re telling you these horrific things that happened to them. It was at this moment, I realized it could have been me. It just so happened that my family moved away from here [and] nobody came looking for us. So, I was struck by the fact that I was lucky. But in doing my research, I came across the fact that I knew one of my aunts had gone to school there, as well as the very man that I was named after, Richard Hill, who was a Tuscarora Chief back in the 1800s, who went to school at the Mohawk Institute. There were many more of my other relatives there when I researched the records. So that helped me to personalize the story,” Hill said. “After interviewing the survivors, particularly some of the older ones who shared their stories, they said something interesting…[along the lines of] ‘Every time I share my story, I heal a little bit more.’ And so that made me feel like this is what we needed to do; to share these survivors’ stories…unadulterated, and remaining true to them.”

Hill then went on to share several stories from the book that touched him to the core.

“There was a man named Bud Whiteye who unfortunately passed away a few months ago [and] he shared his story about what happened to him there…. how he was physically and sexually abused repeatedly, and how he had to deal with that. It really got me thinking that this is just more than just government bureaucracy or just a school and a failed education experiment. This is about what happens to children when they’re suffering repeated trauma, and then how that trauma rolls out through them to them, to their family and to their community,” he said. ”And then there was a woman who shared her story about how the principal was known to abuse young girls. She was so terrified of the principal, she would almost faint in his presence. I have my own daughters, who are ten, 15 and 20, [and] I kept thinking to myself, ‘Imagine something like that happening to my kids? And how would that affect all of us?’”

Despite the tragic and heartbreaking stories, Hill saw how strong these survivors were.

“It’s amazing how resilient the survivors were. They dealt with everything and are now taking the lead to help others understand. One of them was John Elliot—he was this short, feisty man who recently passed away. He would tell stories about how he tried to run away, [starting on] the first day he got there, only to be put into isolation. When we were working on the exhibition, we went around the building with him to decide what it should be like. We got to a little cubbyhole under the staircase, and John looked at the space. You could almost feel him trembling as he looked into the place [similar to] where they used to imprison him. He’s free now, but those scars and wounds ran deep. It was interviewing people like John that made me feel we had more than just an obligation to understand their stories. We had a personal responsibility to represent their stories well in the book, the exhibition, and the film we’re making.”

With the book’s release in early September 2025, Hill is looking forward to getting the book out to the public and using that as well as the exhibition, as a catalyst for healing.

“We’ve started a series of book launches in September, and then we are taking the book directly to the people. It remains to be seen how readers will react, as it’s just been released. However, the manuscript reviews were incredibly positive because this is the first truly comprehensive look at an institution like this. There are over a dozen authors, [and] many people dedicated a lot of time to this, so it’s not just one person trying to go through everyone else’s research. We wanted to represent as many voices and perspectives as we could,” he said. “If people take the time to read and think about [what happened], I believe they’ll finally understand why this all matters and why the Mohawk Institute exhibition is so important. We have to find a way to come to terms with what took place. Then, we want to motivate people to take the necessary steps to begin healing the relationship between Canadians and the Indigenous peoples of this land.”