Before retiring in 2016, Allen Pizzey’s career stretched across parts of five decades, covering major 20th-century events including the Balkan War, the end of Apartheid, and the fall of the Berlin Wall, while gaining a reputation for his exceptional reporting along the way.

Pizzey was born in Brantford, Ontario, and lived in the area for the first eight years of his life before moving.

“When I was very young, we moved away for a little while, because my dad was a telegraph operator way up north on Canadian National Railway…but my first real first memory was coming to live at my grandmother’s house on Gray Street. And then we moved. We moved to another street, and those were my most formative couple of years, because there were four boys [and] we were all friends. We used to hang over the fence in the sixth grade, and anyone who sliced or hooked the ball while playing baseball over the fence, we ran and grabbed it. They would give us a nickel for the ball. I think that’s where I learned you could make money if you were willing to hustle a bit. And it was a lot of fun,” Pizzey recalled. “I also remember when I went to Echo Place School…and close by there was a bridge over the railway….it was wood you could see through the slats. And I was really scared of it, and quite terrified of going over that bridge. And I remember my dad, very calmly taking me over there one day and walking me underneath the bridge. He showed how the girders were just huge pieces of wood, and they would never fall down. There was something about the way my dad explained it to me that melted my fears away.”

Before his tenth birthday, Pizzey and his family moved to London, Ontario, and then eventually to Quebec.

“My dad had then become working the upward chain of office workers. He eventually became an accountant, and we would then move to London and then to Montreal, where I finished high school. I then went to George Williams University, which is now Concordia [and] in my third year, my dad died of a heart attack at the age of 42,” he recalled. “A man down the street from us heard about what happened and wanted to help in some way by offering me a job. He worked for C-I-L, the explosives company. I accepted it because I had to pay my way through school. He got me a job with a drilling and blasting crew around North of Parry Sound…[and] I learned to become a rock blaster.”

Although Pizzey graduated from university with a degree in business administration, he had no desire to work in business.

“During that time, I felt like Benjamin from the movie The Graduate [where] people came up to me, putting their arm around my shoulder and giving me some type of advice…especially people who wanted to be a father figure of sorts….But I would end up calling my old boss, and he offered me a job in Prince Rupert, which is a long way up in British Columbia. I spent a year there living in a bunk camp, making enough money to buy a backpack and deciding to head off to Europe, hitchhiking,” he said. “It was a fun experience. I ended up travelling through 17 countries and even going to Hungary and Czechoslovakia, which was behind the Iron Curtain. It was definitely an interesting time. Hitchhiking was great because that was in 1970…so, there were many backpackers doing the same thing I was doing. Just throwing a Canadian flag on the back of your pack and exploring the world.”

However, Pizzey still had no idea what he wanted to do with his life until he met someone who pointed him in the right direction.

“I didn’t really know what I wanted to do, but I knew what I didn’t want to do, which was to work in an office or in business. There were a lot of things in the world that were interesting to see, and there was a lot of fun to be had as I experienced hitchhiking. I would go on to meet a girl in Europe. We hitched through several countries and went back to Canada….to make some money and then head off to South Africa. We decided to get married, and I got a job selling soap for Procter & Gamble, driving to businesses in Ontario. I hated that job, but that got me enough money to travel to South Africa. My fiancé was already there…So, I decided to hitchhike and ended up taking a ship over. I shared a cabin below decks with five other men, and one of them had been working for the Cape Times.” Pizzey recounted. “He told me stories about his daily adventures as a journalist, which really appealed to me. His stories brought me back to when I was a Boy Scout, and going on a trip to a newspaper in Ottawa. We were taken down to the press room by the President of the paper. I remembered staring at those huge presses. It started with the paper going into slow roll and getting faster and faster until the building shook and roared…and then the newspapers came out printed and all folded. I loved experiencing that. And that journalist’s adventures got me thinking about that time in my childhood.”

When he got to South Africa, Pizzey had no money and immediately started looking for work.

“The local afternoon paper was looking for an advertising rep, which I applied for and got. Naivety is a wonderful thing. I planned to get that job and then just change departments, where I could do stories. But it didn’t work out like that; it was fun for a while. Around that time, I broke up with my fiancé. We had made some trips around Southern Africa in a camper van and into the wilds [and] realized that we liked being together, but we weren’t suited for marriage and went our separate ways,” he recalled. “I would go on to write a story about Czechoslovakia post Prague Spring. I gave it to the deputy editor of the paper, who commented positively…it had good grammar and said that I wasn’t a bad writer. Though there was no job available as a reporter, I was insistent. I really didn’t like being in advertising [and] eventually I would get a chance to be a reporter after continually checking in to see if there was a position available. He wanted me to stop bothering him, so that’s how I got started as a reporter.”

Pizzey adapted well to being a journalist and enjoyed the fast-paced career.

“I just took to it. I just love doing it….one of the things that helped me in my career was working for great people and just focusing on sharing the truth with readers. At one point, the city engineer of Cape Town publicly called me an enemy of the people of Cape Town because of the story I wrote about how the road projects that they were heading were all doomed…Then I wrote another one about the plan to desecrate a place that was called the Garden Room, which is up the coast of the east coast of South Africa, and build a highway in its place. I then did a whimsical little piece on the cheap brands of wine by one of the major wine producers in the area, which] was not taken well. They threatened to withdraw advertising. So, I was summoned to the [editor’s] office. He stood there holding an envelope, which I thought was my pink slip. He told me that I gave him a lot of trouble. I was apologetic and asked who I had offended this time. He then handed me the envelope…[and] it wasn’t a pink slip. Instead, it was a 6% pay raise, which was effective immediately. I was very thankful and waved me off and told me to offend someone…as he knew he would be dealing with them,” he recalled.

However, the budding journalist would finally find his career path during a conflict.

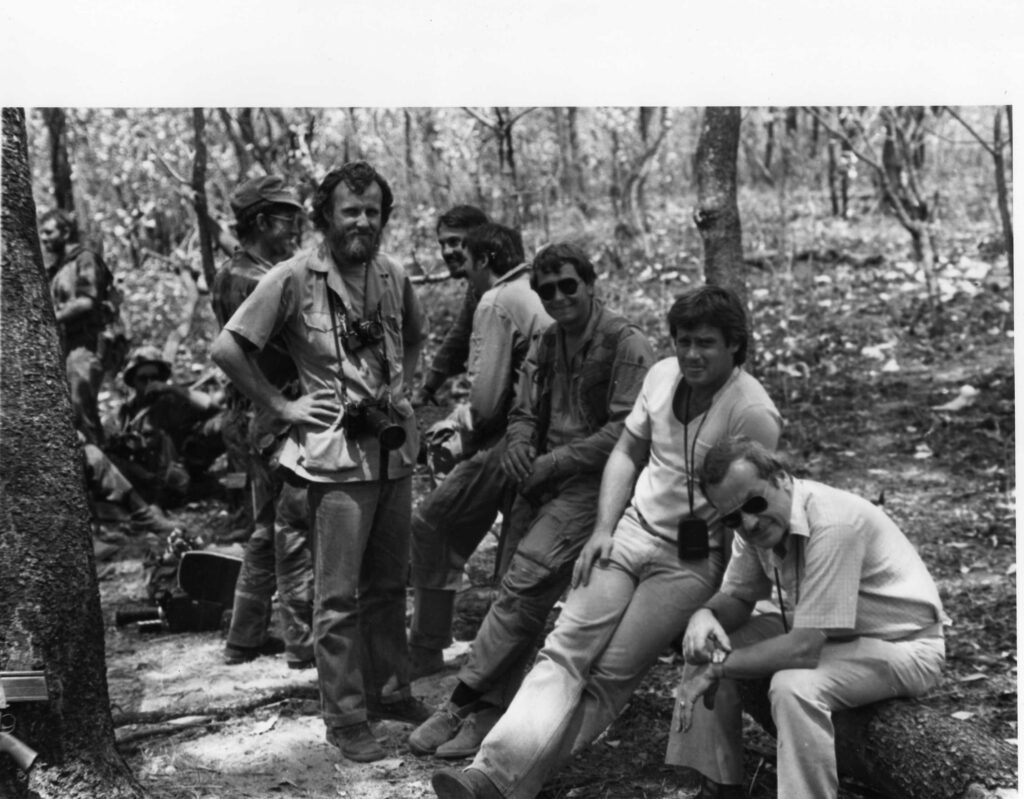

‘The newspaper had a bureau in Nairobi to cover the east and that part of Africa. I went to work there, and under the greatest editor of work for my life….I had to learn all kinds of things, like how to use a Telex machine because there was no internet, no computers, and no cell phones. He sent me off to cover many different stories,” he recalled. “Then the civil war in Angola was raging. I spent several months in and out of Angola [and] got shot at, and threatened [and] saw horrible, horrible things. But we were on the front page almost every day, and the stories were great [as] they were human stories. It was scary being in the middle of that, but I knew these stories were important and they needed to be told. And somewhere in the middle of all that, I realized this was what I want to do….I wanted to be a foreign correspondent. I want to do this forever. That propelled me in this career.”

In this conflict, along with other wars he would report on, Pizzey discovered many truths.

“Wars are always at the top of the news. But more than anything, when you are reporting on them, you see everything in life. You see the best and the worst of humanity. You see cowardice and the evil that people are capable of. On the other hand, you also see people who are very brave and extraordinarily generous, and you see resilience of the human spirit…and other times you would ask: how do you keep going? How do you cope with this? People do, and they help each other,” he noted. “I remember, when the Kosovars were driven out of southern Serbia into Macedonia by the Serbs and the Macedonians confined them…a group of them, hundreds of them, in a muddy field with no shelter. They wouldn’t let the press in, but we managed to sneak in where the bread truck was delivering some food. We were walking among them, and I remember a man sitting on the ground in the mud with his wife and a couple of kids. All the possessions that he owned in the world were there, with him in the mud, which wasn’t much. And he had bread that had been given to him as a handout. He then offered me a piece of bread, which stunned me as he had little food for himself and his family. He simply told me that was what you were supposed to. That was very moving.”

Another inspiring story was about a Croatian girl that Pizzey reported on, who would inspire many people.

“When we were driving into Sarajevo… I came across some aid workers who told us there was a group of Bosnian Muslim refugees, and they were stuck in a Croatian School up on the hill, and they couldn’t escape. For the weekend news piece, we were given a chance to tell a human story. We met a child up there named Yasmina, and] she spoke fractured English. She took us all around, and she told us her story. These people were all living on little thin mattresses, all jammed together in this abandoned school. Yasmina told us a story about how she had this lovely house [and] were driven out of their home by the Serbs, and on the bus, people had been shot. Her mother couldn’t tell the story because she simply broke down. Instead, Yasmina did. We found that she [encapsulated the experience of] every refugee in this war. I called CBS and asked to delay the story on Sarajevo, mentioning the girl we had just met…wanting, instead, to give us some more time to prove what this kid told us was true. If we could, it would be a great story,” Pizzey recounted. “We drove all the way back. We went into the area where she came from. Despite some roadblocks…we got a wonderful translator who persuaded them to let us into the prison to interview the girl’s father. And it turned out that what she told us was true. Our story would resonate with people, and this one man had seen our story and told us he wanted to help Yasmina and her family. He got his congressman involved [and] eventually, got everything together…the father was released from prison, and the family all got together in the transit camp, and they got visas to go to the United States.”

However, Pizzey also experienced the anti-Apartheid violence and how people overcame it.

“I’d lived in South Africa, [and] worked on the newspapers down there for two years. I understood the people, understood the history. I liked the country, and I worked with some of the best camera crews there. After covering this, it was obvious the black [population] was going to win, because they would not quit. They took to the streets, knowing full well that they could be shot, and they did it over and over and over again,” he stated. “But what the moment that sticks out in my mind most was when Nelson Mandela was inaugurated. Rather than anchoring the story, I wanted to be on the steps the government offices in Pretoria where he was going to be sworn in, covering it that way….we were left down on the lawn where there were 1000s of people, and when he was sworn in, the whole place erupted. People were singing, dancing, and hugging…all the racial groups were together…and the white apartheid regime that had formed to keep people apart disappeared. Everybody was happy together. We had seen so many horrible things during the violence and now we were witnessing a historic event. There was no place I would rather have been at that moment, no people I would rather have been with more at the moment then with those around me.”

One of the stories in which Pizzey captured an award for, was his story on a rescue of dozens of people from a gulf tanker during the start of the Iranian-Iraq war in 1980.

“We would go up there for months…flying for hours around in Huey helicopter looking for ships being attacked by gunboats from both sides. We used to sit and listen to channel 16, which has been the main hailing frequency for ships at sea. And one day there was a Mayday. A supertanker was hit by a rocket on the side by the Iranians …so, we jumped in our helicopter and flew out, and there to the ship. There was about a kilometer long river of fire behind the supertanker with oil burning. And they were there these men on deck with the US military helping winching them onto a helicopter, taking them off three at a time….there were about 40 people on the tanker,” Pizzey recalled. “They called all the pilots [in the area] who were mostly ex-military, and they asked us if we could help pull the others off the tanker. We landed on the deck of this burning tanker six times,…taking as many people as we could. As we got off, we stayed on the deck of the tank and interviewed the captain. We recorded a really good story, while doing a good deed by pulling a total of 29 people off the ship. There were half a dozen press helicopters in the air, [but] we were the only ones to land on the ship [and] that meant that all the other TV networks…had to put our [exclusive] film in their stories, which drove them nuts, and we loved that.”

Another memory that sticks out in Pizzey’s mind was the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

“That was really interesting to cover, because the press was not allowed into East Berlin…so we would go across Checkpoint Charlie, which was the one place you could cross…, and we go across in rented cars, or we’d walk across and we’d pretend to be tourists, bringing little cameras along. And then we went to illegal secret meetings [and] demonstrations. We would smuggle these recordings on video tapes across Checkpoint Charlie. It was pretty nerve wracking, but all of sudden the wall fell. And all that intrigue disappeared. It was an extraordinary moment of joy when that happened…and people simply went over the Berlin wall when it fell,” he reflected.

While Pizzey has reported on war and conflicts through his decades-long career, he relished his experience in doing stories that revealed other positive aspects of life.

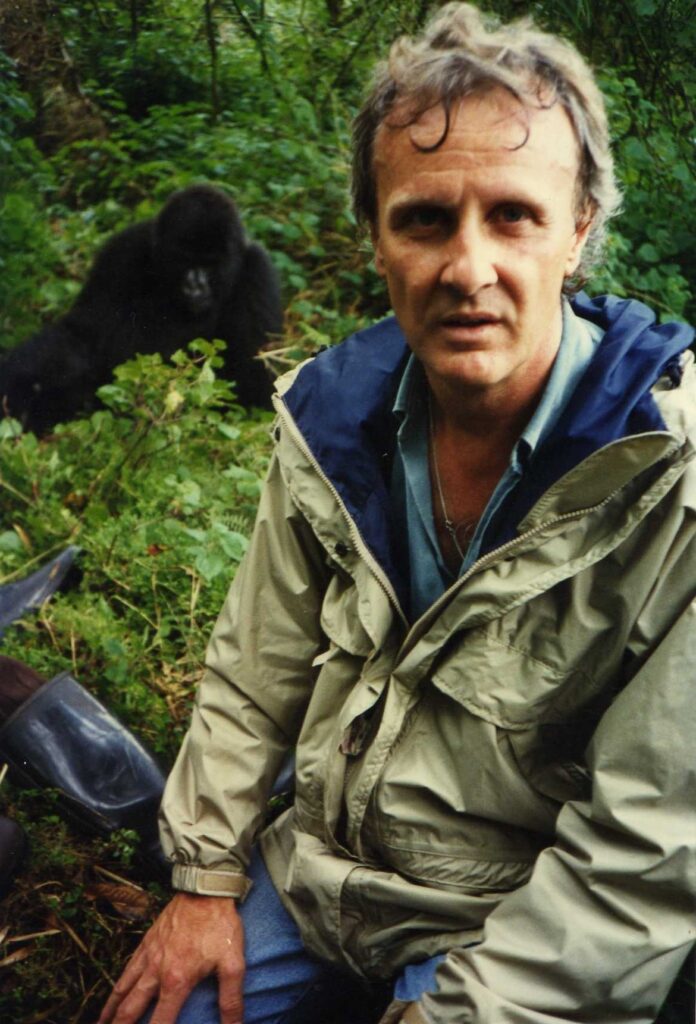

“I loved doing stories for Sunday Morning on CBS….because you could do long, intelligent pieces. I got to do a story on how you make parmigiano cheese, and another on how they build Ferraris. I got a chance to drive one which was pretty fantastic. But the best one of all was when we went to cover the National Park, and we went to the group of mountains. We went with a team that studied in the area….[it was remote.] We made our way to a place where Silverback Gorillas were. And about 15 or 20 feet from me was the alpha male of the troop, a 400-pound Silverback Male Gorilla. And he was just sitting there and I looked at him under my hands and knees, and he reached there. He snapped off a piece of bamboo….and then looked at me. I really wanted to ask him a question….because of the intelligence that I saw in his eyes,” he said. “And then, we went on the evening surprise. We rode on elephants. I got to sit right behind the elephant’s head [and the elephant handler] sat behind me instead of in front of me. My feet were spread across this elephant’s neck with my legs behind his ears, and their skin is incredibly rough…but it was just it was magical experience.”

Nevertheless, Pizzey also saw how technology as well as platforms like social media has affected news.

“As technology improved it made the job easier to do in many ways, but harder in others, because the faster the news was available, the less time you had to think about creating it. And the demands of live television, I believe, became ridiculous. People wanted ‘live’ for the sake of being ‘live’… I’m glad I’m retired, because I think that the takeover of American networks…by major corporations who then cow two to politicians because they want to make money,” he explained. “I think good reporters try to keep the news truth based. If you’re a journalist, you just have to keep adhering to the principles that we work under [because] truth is sacred. We just have to maintain our integrity and do the best we can. If you’re a reader or a viewer, you need to consult multiple sources. Look at the agenda of your news source that’s presenting it, and you’ll have an idea what they’re talking about, if you can pay attention to violence [you can most certainly] pay attention to the people who are presenting [and] bringing you the news, and you’ll learn whether or not you can trust them.”

After enjoying a career with many highlights, as well as many challenges, Pizzey decided to retire from CBS News in March 2016. The strain was affecting him physically, yet from retirement a new opportunity to ‘report’ on the world emerged.

“I was approaching my mid-60s [and] if I was going to continue to go to all these places, I needed to be in pretty good shape with all my senses because I was part of the team. I didn’t want to be in a position that I would endanger my team because I couldn’t continue the [physical demands of the job.] Also, I was just getting a little fed up with the way things were changing and the demands were being made upon us, and I didn’t like it, so I but I knew I couldn’t quit cold turkey….[so] I stopped being a staffer on call, 24 hours a day, seven days a week. I took a contract where I was guaranteed 100 days’ work a year, and every day after that was paid at a freelance rate. Then, I slowly tapered things off. And then when I was 69, I thought that was long enough and decided to retired….but somewhere in the back of my mind I knew I had been lucky for a long time, and when my friends were killed in places like Baghdad, one of the things I wrote was that for journalists who cover conflicts, they are like blind trust funds. They can make withdrawals, but there are no deposits…and you have no idea how much time is left,” Pizzey said. “I got lucky a lot of times…but as I was considering retirement, I wondered how long would this luck last? It was maybe time to step away. But I couldn’t really fully stop…so I ended up starting my blog, ‘Pizzey’s Perch.’ Blogging is nice because….as a journalist, you don’t really have opinions… you present the story and let other people make up their minds. But if you’re a blogger, I would now get a chance to tell you my opinion and write about whatever is on my mind. And that’s fun and I really like doing that. And that gets to where I believe journalists never really retire. They just change the way they carry on with their craft.”