For John Macdonald, the importance of advocacy for Indigenous rights and causes, as well as coaching and education, and supporting programs like those for Truth and Reconciliation, has made him a key community leader across the County of Brant, Six Nations of the Grand River, and Norfolk County.

Macdonald, who is part of the Six Nations of the Grand River, Mohawk Wolf Clan, grew up in Simcoe in Norfolk County.

“I have a neat pathway. I’m half Native. My mom’s from Six Nations and my dad’s from Caledonia. We lived along the river…my sister and I both had awful respiratory issues, so we had to move to a town that had a hospital in it [and] my parents chose Simcoe. As a young person, I didn’t have any access to football…[and] it wasn’t convenient to get to, because we would have had to drive all the way up to Brantford. That being said, I played soccer and hockey as a kid, but I was quite a burly kid…I was about as wide as I was tall. I was always a good athlete, and I remember in grade five, I ran the 60-meter dash, and I came first, even though I was the biggest kid there. I always had that super power of speed with size,” MacDonald recalled. “My father has always been a football fan. We were Hamilton Tiger-Cats season ticket holders. Starting in Grade 6 (all the way through Grade 12), he sent me to football camp for one week every summer…which was at the University of Guelph. During my first year playing offensive line, the coaches told me I needed to work on my pass block. I remember lining up against a guy and knocking him over. I then knocked him over again and again. The coaches were so excited. I remember thinking to myself, ‘Is this what football is all about? It’s easy!’ That initial feeling of success from the week-long summer camp was my real introduction to football.”

In high school, MacDonald would quickly become a stand-out defensive player.

“The football camp, run by university coaches, gave me a great foundation and a fantastic experience. The camp even featured NFL players like James Boston and Daryl Johnson, who spoke to us about training and character. I would go on to attend Simcoe Composite School (SCS). Unlike today, you just went to the school in your town, and since I played rep hockey and soccer, I knew most of the kids. In grade nine, I tried out for the varsity football team and was absolutely demolished by a senior,” he said. “When I went home, my ankle hurt, and I was beat up. My mom [pressed me], ‘Well, what are you going to do about it?’ And that served as my motivation. I [also] decided to follow the camp coaches’ advice to start training. I immediately got a membership at Iron Masters Gym and worked out consistently for a year, all while still playing other sports like hockey, basketball, and doing track and field. I didn’t actually play on a real team until grade ten. By then, I would become a starter right away—I had been six-foot-two in grade nine, and by grade ten, I was a big kid at about 275 pounds.”

At SCS, Macdonald was surrounded by good coaches, who provided him with a strong foundation in his growth as both a football player and a leader.

“I was really fortunate to have Dave Abbey there, who was the head coach of the football team. He had played offensive line for the University of Toronto and was a good position coach. He eventually became a local superintendent [at the Grand Erie District School Board]. Then, in Grade 11, we got a new offensive coach, Ken Morgan, who eventually became the head coach. He was just a great disciplinarian, a real tactician, and incredibly organized,” Macdonald said. “That same year, we won the championship. Abbey was still the head coach, but Ken Morgan was our offensive coordinator. We ended up beating a Valley Heights team. 26-21, just the year before, had absolutely crushed us 66-0 in one game. The championship was huge for us. We hadn’t won a title in 15 years, so it was a major event for us to come from nowhere like that. Ken, as it turns out, was a bit of a legend in Norfolk County. In his 30 years of coaching…he only missed the championship game twice. Coach Abbey helped me with the position fundamentals, but Ken was a major influence on me; not just as a player, but eventually as a coach, just by seeing how he ran things at the high school level.”

For Macdonald, who would win Simcoe Composite’s Male Athlete of the Year in his senior year, was more focused on playing sports rather than on his own stats. But the ultimate goal was to become an educator.

“Even though I love playing sports, I wasn’t a big sports fan. I wasn’t the type of guy to watch sports all the time, so I really didn’t understand things like statistics. There are some instances in high school where I would be mad at myself if I didn’t make every single tackle on the drive, and in hindsight, that’s unbelievable to think that way and, at times, achieve that. At that point, in terms of comparison to other players, I hadn’t played for Brantford or the Bisons, and I never played on an all-star [team]. I was playing down in a little school in Simcoe, and everyone around me was telling me I was just too small to play University. So, I just continued to do my best and train,” he said. “[While I played a lot of sports…] my parents were very school-oriented, so it was always school first and the sports were second. I was always doing well in my classes. I was also involved in theater and band. Football wasn’t really something that I thought was a possibility. By the time I got to Grade 13, my coach, Ken Morgan, told me I could play football [at the university level.] He started to call all these schools…recruiting was so very different back then. There was no YouTube. It was all word-of-mouth. By the time people started hearing about me…a couple of scouts came and saw me playing during my last year from local universities like Guelph and McMaster…I got a letter from the majority of the universities in Canada. So that was pretty neat…I was really overwhelmed by the process, but even with all these offers to continue to play football…the pathway for me was to become a teacher.”

MacDonald would commit to Wilfred Laurier University; however, he would decide to visit McGill University in Montreal, where he felt a personal connection.

“The stars truly aligned for me at McGill University. The school has a great Scottish history, which aligned perfectly with my last name, ‘Macdonald’, which was [appealing.] When I arrived on the lower campus, I saw a rock with a carving that read, ‘This is the site of the Iroquois Village of Hochelaga.’ I realized the school was part Scottish and part Native, all located in the amazing city of Montreal. Since my parents were splitting up at the time, I also welcomed the chance to start my new life somewhere fresh. That combination is precisely how I chose McGill,” Mac

Although the coaches knew of Macdonald’s potential on the field, he was still not as highly ranked as other prospects.

“I entered the recruiting roster as a question mark. Apparently, I came to find out that all the recruiters talk to each other, and my coach had spoken highly of me, noting my potential to play university-level football and my excellent grades. But without any film or comparison, I wasn’t a ‘blue chip’ guy. On my recruiting trip, after meeting the other players and coaches, we went into the gym. The assistant coach, [and] the offensive coordinator asked me to demonstrate bench pressing as an introduction to lifting for the other guys. I put 225 pounds on the bar and repped it out five or six times, then did the same with the squat. The other rookies’ eyes went wide. I could tell the coaches were thinking, ‘We might be onto something here.’ When I finally got to training camp my rookie season, I benched 320, and ran a 4.9 forty. I also weighed about 240. I did all the physical stuff really well and realized for the first time that I could truly play at that level,” he explained.

However, Macdonald would play with various players who would go on to the CFL and even the NFL.

“I wasn’t worried about the defensive depth chart, even if there were a dozen guys ahead of me. I developed quickly during my time there, playing alongside many talented individuals—about ten of my teammates went on to play in the CFL. We were in an excellent football conference that featured powerhouses like Laval and Ottawa, who were perennial Vanier Cup contenders. I [also] had incredible role models and teammates, including Jean-Philippe Garcia, a snapper who played in the NFL and is now a doctor for the Kansas City Chiefs. My linemate was Randy Chevrier, a long snapper who was drafted in the NFL and played in the CFL for 12 or 13 seasons. We also had Matt Nickel on the defensive line, and I played with Samir Chahine, a great friend and multi-year CFL offensive lineman. Though we struggled initially, losing in the first round of the playoffs my rookie year, I [would] become a starter by my second season and steadily gained weight and strength. By my fourth and final year, we had an incredible run, starting the season 5-0, but we ended up losing the last three games and then fell to Ottawa in the first round of the playoffs, who ultimately went on to win the Vanier Cup.”

Macdonald started to develop a strong reputation for his defensive abilities, leading him to be called ‘The Prime Minister of Defence,’ but a serious injury would put a damper on his otherwise solid university football career.

“The year before, I led the team in sacks and looked like it was going to be a great next year for me. Unfortunately, the following year, my season was cut short. I tore my ACL and only played five games. Even so, when the injury happened, I was leading the CIS in sacks and was still named a Second Team All-Canadian despite the limited playing time,” he reflected. “My recovery was a massive undertaking. I had my ACL reconstruction [and] immediately went to train with Matt Nichols to get my knee back up to snuff. I was determined to prove myself [that I could play again], and the hard work paid off. By March, I was at the CFL Combine. I ran, did the bench press, [and] participated in every drill. I had rehabbed like crazy to get myself back into shape, and by May, I was ready to play. All of this was happening while I was also focused on my studies. I had completed my BA and was in the first year of a two-year Bachelor of Education program when I was drafted.”

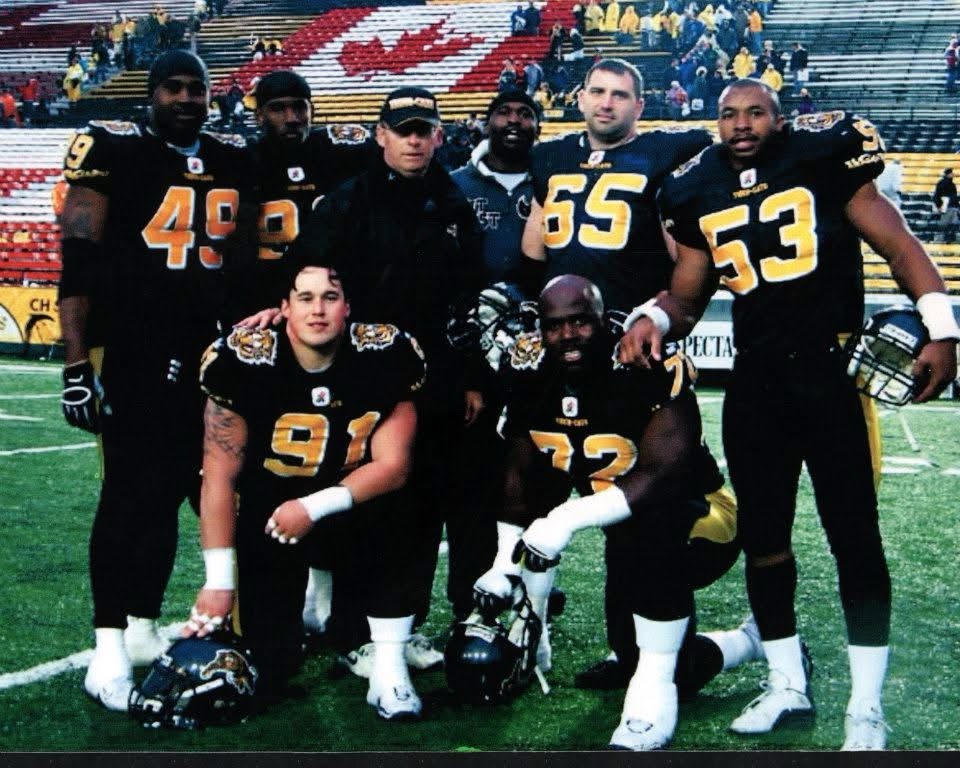

In 2001, he was drafted in the first round by the Hamilton Tiger-Cats, a team he had grown up watching as a season ticket holder with his father.

“The organization saw more than just my game film; [the team] spoke to the media about my recovery. When asked if they were worried about my ACL reconstruction, [they] said: “Any player that works that hard to get himself back in shape after an injury like that shows he’s a hard worker. So that’s what we want.’ I was actually drafted because of the aftermath of my ACL reconstruction. My work ethic and commitment to getting back on the field convinced them I was the kind of player they wanted,” he said. “My first CFL season was a steep learning curve. I came from Canadian university football, and the leap to the pros was massive. I felt completely in over my head. To make things more challenging, I spent the entire season dealing with a significant back injury. I played almost every rep in training camp because the team wanted to get me ready, but between that and the pain, there were nights I was almost in tears. Despite my personal struggles at the time, I was surrounded by talent. I ended up starting on a defensive line that featured Joe Montford, Johnny Scott (a CFL All-Star), and Tim Cheatwood, who would also become an All-Star. I played right beside Tim. Unfortunately, 2003 was a tough year for the team. We went 1-17. We lost key players like Danny McManus and Rob Hitchcock to injuries, and we struggled immensely.”

During his time in the CFL, Macdonald had a focus on his education and eventually became a teacher. That meant juggling the rigors of a professional football season and his studies.

“After my first CFL season, I still had a final year of my teaching degree to complete. Since the season runs through the fall, I reached out to every professor for my registered classes and asked for a special arrangement…like completing the coursework via distance education. I offered to do the readings, organize all my materials, and email in my papers, just so I wouldn’t have to put my education on hold. Every single professor was incredibly supportive, believing my experience as a pro athlete would enhance the way I would teach. This arrangement was critical because I only had two months of classes before my teaching placement started in November,” Macdonald recalled. “As fate would have it, my CFL season ended at the perfect time. The final game with Calgary was against Toronto; a win meant the playoffs, but a loss meant the season was over. We lost. I immediately got in my car, drove back to Montreal, and started my teaching placement that Monday. This allowed me to continue playing without interrupting my final year of Teachers College at McGill. I was able to train in Montreal that off-season with other CFL players, including Tim Fleiszer (who is now the Executive Director of the Concussion Legacy Foundation Canada)…[and] Randy [Chevrier]. Going into my second year, the starting defensive tackle ahead of me held out for more money and didn’t get it. I showed up to training camp, and they told me: ‘You’re the starter.’”

Nevertheless, even being a starter, Macdonald knew his professional career was going to be a short one.

“I was often on and off the injured reserve list as the team began to groom new American players to eventually replace older veterans. After that season, I declared for free agency, having played out my contract. That off-season, I was offered a full-time teaching contract at Waterford. I talked with my girlfriend (who is now my wife) and made the decision…I wanted to be able to coach my kids and be a high school football coach without being crippled,” he said. “Even as I started teaching, I received calls from teams like Ottawa, but I told them I was done. I already had a foot in the door with teaching, having done a long-term occasional placement between the 2003 and 2004 seasons, as well as supply teaching in the Six Nations community, which was very rewarding. I bought a house in Caledonia and decided to cash in my chips while I could still walk and begin my new career.”

Macdonald was on his way to the start of his career in education, recalling his parents and how they set the stage for his success, especially dealing with a diagnosis that could have been an albatross.

“Sports have always been central to my life. When I was diagnosed with ADHD in Grade 3, my parents adopted the philosophy that I just needed to keep busy. I’ve come to see that diagnosis not as a hindrance but as a blessing, as my high volume of activity has remained constant. My grandmother reinforced this: ‘You always gotta keep busy. If you’re not busy, that’s when you get into trouble.’ I’ve always been doing something, and this drive [has] shaped my career. It was at McKinnon Park that I began teaching Native Studies and English, which marked the beginning of my Indigenous advocacy pathway,” the veteran coach said. “My teaching career began at Waterford High School. Naturally, I started coaching football—I couldn’t teach high school without coaching a team [and] I would coach Shane Bergman. I coached him that season, and he’s now a good friend of mine. We recently completed a football program together at the Sprucedale Youth Centre, maintaining our friendship even after he became a Grey Cup Champion. I coached the line that year, and we had a phenomenal team that went 9-0.”

Macdonald would go on to teach in Simcoe, gaining an invaluable foundation in teaching, and eventually leading him to Brantford.

“Throughout my career, I’ve always believed that teaching and coaching are interconnected. My primary motivation has always been to be an [engaging] teacher, but if you’re not involved outside the classroom, the kids know it. When you are involved, they are more respectful and aware of your commitment to the school community. They see that you’re about more than just the subject matter, making them more likely to follow instructions and listen in class. Coaching, teaching, and being a good role model all work together. After two or three years at McKinnon Park, I became deeply involved in the Indigenous Education Committee. This led to a two-year role as the Indigenous Education Teacher Consultant for the entire school board,” Macdonald said. “I [then] coached at the University of Guelph with Kyle Walters (now the General Manager of the Blue Bombers, and whom I played with on the Tiger-Cats). This coaching role allowed me to coach twice a week and attend games, keeping me involved in football without the daily high school commitment. In my consultant role focusing on the non-reserve Indigenous population in and around Brantford, I worked extensively with elementary feeder schools in areas like Eagle Place. My heart went out to these students and the teachers serving them. I supported Pauline Johnson Collegiate as a consultant and, when the head of English position became available, I knew it was the right place to have a positive influence on the local Indigenous community. I applied, believing I could make a significant impact given the educational climate at the time.”

After a few short years at Pauline Johnson Collegiate, Macdonald had a positive impact.

“At the time, we were competing in the Brantford loop against much larger schools like Assumption College and Brantford Collegiate Institute, which had numbers that dwarfed our 750 students. We struggled to field a [viable] team, often having only 25 players per junior and senior squad. After a few years, and following the retirement of Head Coach Ken Chisholm, I took over. Recognizing that we were always considered the ‘younger sibling’ in the Brantford league, I proposed a shift. I believed the team would have a more competitive and positive experience if we moved to the [Athletic Association of Brant, Haldimand and Norfolk (AABHN)]. In an exhibition game against Holy Trinity, where we easily could have won 60-10, confirmed to the players that we were in the wrong league. I told them that we were not a bad football team…we just didn’t have enough players to last,” he said. “Since making the switch post-COVID, we’ve been competitive every year. By combining our junior and senior players (Grades 10 through 5th-year students), we now field a viable team of 50 to 60 players. This represents about ten per cent of the boys in the school; a remarkable participation rate for any high school. The move paid off dramatically in 2022 when we won the local championship. Last year, we were a top-three contender. I love what I do here, teaching these great kids the fundamentals of the game, instilling character, and helping them fall in love with football.”

While Macdonald has focused on building communities through mentorship, coaching teams, and being a positive role model, he has also been recognized for his efforts and dedication through the years, being inducted into the Norfolk Hall of Fame in 2017.

“My induction into the Norfolk Hall of Recognition was a wonderful honor, particularly because I was the first football player to be inducted. The success I found playing football at McGill University sparked a chain reaction back home, almost creating a feeder system into Montreal. Two years after I left, my good friend, Jim Merrick (who is now principal at the Delhi District Secondary School), came to play at McGill with me. His younger brother went to Concordia, along with about three other players from Simcoe,” he reflected. “My success proved to the kids in the area that being from a small town doesn’t preclude you from achieving big things. It was gratifying to be a trailblazer for football in Norfolk. I credit my work ethic to the farming culture and values ingrained in the Norfolk community. Both of my parents came from farming backgrounds—my maternal grandfather was a farmer on the reserve, and my paternal grandfather was a butcher. That strong work ethic is something I feel is inherent in Norfolk. It was a great feeling to be recognized there and to acknowledge the significant contributions of my coaches and the community to my success.”

In 2025, Macdonald was inducted into the North American Indigenous Hall of Fame, an honor that touched him on several levels.

“My induction into the North American Indigenous Hall of Fame was a humbling surprise. The work I do, providing mentorship, offering programs, and supporting the Indigenous community, is deeply personal to me…Indigenous people are fundamentally sports people. I later learned a fascinating history that reinforces this connection [from] a book by Sally Jenkins, The Real All-American, which details the contributions of Indigenous players to football. It focuses on the team from the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, where legends like Pop Warner and Jim Thorpe played in the early 1900s,” he explained. “Lacking the physical size of their opponents (like Yale and Harvard), these residential school students became innovators. They are credited with inventing the play-action pass—faking a run to throw the ball deep—to counter the ‘smash-mouth,’ rugby style of the larger white teams. This history of using ingenuity to compete is something I was unaware of for most of my life…. [and now] to be listed on the Hall of Fame website alongside some of the incredible names in Indigenous sports and advocacy is truly humbling. It was also wonderful to share the experience with my wife…the induction ceremony was held in Green Bay on the Oneida territory, one of the Six Nations. That weekend was a lot of fun and a profound honor.”

However, for Macdonald, it all comes down to being a teacher in the community and providing leadership for the next generation.

“I’ve always been taught by elders that…the priority should be serving your own community and being on the grassroots level. So that’s my priority with what I do daily basis here in Brantford…not [only] with the Six Nations, but all over the communities. So, the recognitions are nice, but what keeps me going every day is working with the kids. That’s what I love to do,” concluded Macdonald.